LADWP released the following preliminary report regarding the performance of its water system during the Palisades Fire. The report includes a description of the Palisades water system, the Santa Ynez Reservoir, the department’s response to the fire, efforts to mitigate loss of pressure, and an update on the reservoir cover repairs. Please note this is a preliminary report that is necessarily limited in some details due to ongoing litigation. Additionally, LADWP continues to cooperate fully with the State in its efforts to conduct an independent review into the January windstorm and wildfire event.

I. Overview of the Palisades Water System

In general, the flow of water into the City begins at its north end, in a filtration plant. From there, water is released into “trunk lines”-essentially large pipes-that run throughout the City. The trunk lines connect to smaller pipes that deliver water more locally to homes, businesses, and fire hydrants. All water that runs through this system, including to hydrants, is potable. There are not separate distribution systems for drinking water and hydrants.

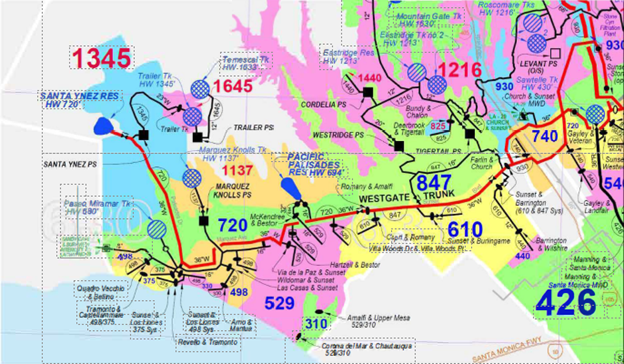

There is one trunk line, called the Westgate Trunk Line, that brings water from the east into and through the Palisades. In Figure 1 below, the Westgate Trunk Line is shown in red and runs through the middle of the map:

As water runs through the trunk line, it is distributed along the way into “pressure zones,” which are divided by elevation. In Figure 1, low-elevation zones are numbered in blue ( e.g., 720) and high-elevation zones are numbered in red (e.g., 1345). Water flows to low-elevation zones largely through gravity. For high-elevation zones, water is directed through pumping stations which allow the water to flow upwards against gravity.

There are three pumping stations in the Palisades: Marquez Knolls (“MKPS”), Santa Ynez (“SYPS”), and Trailer (“TPS”). In Figure 1, these are depicted as square, black boxes; they are found in zones 720, 1345, and 1645, respectively. The pumping stations pump water upwards into tanks, which store the water for further distribution into their corresponding zone. The pumping stations need sufficient water pressure to work; otherwise, the pumps lose their ability to suction and shut down to avoid cavitation.

The three pumping stations direct water into three tanks in the Palisades. MKPS pumps water into the Marquez Knolls Tank, SYPS pumps into the Trailer Tank, and TPS pumps into the Temescal Tank. Figure 1 shows the three tanks as mesh blue circles in zones 1137 and 1645.

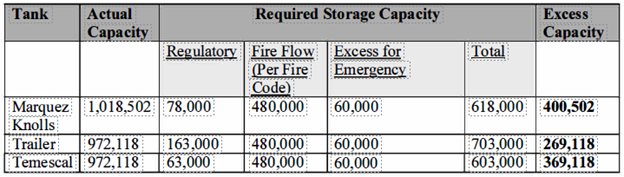

Each of the three tanks holds roughly one million gallons of water-more than required by the applicable regulations and guidelines. Each tank must be able to hold a sufficient amount of water in regulatory storage, fire flow storage, and total emergency storage. Regulatory storage is the amount needed for regular usage by customers in the area, which LAD WP calculates based on historical usage patterns. Fire flow storage is the amount needed for use in a fire. This amount is set by the Fire Code; for low-density residential areas like the Palisades, there must be enough storage to sustain three adjacent hydrants flowing simultaneously at a combined 2,000 gallons per minute. 1 And emergency storage is the amount needed for fire flow plus a sufficient excess to account for emergencies. Figure 2 below summarizes each of the three tanks’ storage requirements. As you can see, the Marquez Knolls Tank exceeded its minimum requirement by 400,502 gallons, Trailer Tank by 269,118 gallons, and Temescal Tank by 369,118 gallons.

Figure 2

L.A. City Fire Code § 507 .3 .1.

As reflected in Figure 1, geographically the Palisades pumping stations and tanks sit near the end of the Westgate Trunk Line. This means water reaches the pumping stations and tanks only after it passes through the low-elevation zones. When water is in high demand in those zones, it moves very quickly through the pipes, which causes pressure loss due to friction loss. In other words, as the amount of water flowing out of the system increases, the velocity of the water flowing through the system also increases. That increase in the velocity of the water flow causes a reduction in pressure. If the water loses too much pressure, there could be too little pressure to create the suction necessary for the pumps to work. This, in turn, can affect the pumping stations’ ability to supply water and pressure to the high-elevation zones.

Finally, at the western end of the Westgate Trunk Line sits the Santa Ynez Reservoir (“SYR”). SYR is depicted in Figure 1 as a solid blue circle in zone 1345. When in use and connected to the potable water system, SYR can receive and store excess water from the trunk line for later distribution, creating a redundancy in the system. There is an additional reservoir depicted in Figure 1, the Palisades Reservoir, which is shown as a solid blue circle in zone 1137. This reservoir was taken out of service in 2013. At that time, the Palisades Reservoir suffered from pervasive water quality concerns and leaks, and the reservoir was not needed to satisfy system demands.

SYR has a stated capacity of 117 million gallons. At most, however, only about 60 million gallons is usable through the water system. This is because, like all reservoirs, SYR cannot practically be operated above or below certain levels. At the top end, SYR cannot be filled more than 705 feet above sea level, or else there is a serious risk of nitrification and water quality degradation. At the bottom end, SYR cannot be operated less than 670 feet above sea level (and even that low level is achievable only in serious emergencies), or else there is insufficient pressure to push water out from the reservoir and into the distribution system. This difference between the reservoir’s maximum and minimum levels is called the “operational band,” and translates to a maximum of roughly 60 million gallons of water for SYR. The Palisades Reservoir has a stated capacity of 6 million gallons and, when it was in use, an operational band of approximately 1. 7 5 million gallons.

II. LADWP Response to the Fire

A. Before the Fire

Shortly before January 7, 2025, the National Weather Service issued a Red Flag Warning that warned of high winds and low humidity. As is LADWP’s typical practice in these situations, the department filled all functioning tanks and reservoirs throughout the City as much as possible. LADWP also ensured pumping stations had backup power in place in case power was lost during a fire.

B. Pressure Loss During the Fire

On the morning of January 7, 2025, the Palisades Fire ignited. From its inception, the fire spread extremely quickly through the Palisades.

The fire’s swift spread led to extraordinary demands on the Westgate Trunk Line. Given wind conditions at the time, firefighters could not fight the fire by air, so they used water drawn solely from the trunk line. Residents, too, drew on the trunk line by turning and leaving on sprinklers while evacuating, using hoses on their houses, and leaving hoses running. In addition, as structures burned, damaged or opened premises pipes leaked more water.

As water from the Westgate Trunk Line was used at extraordinary rates, water pressure rapidly decreased. As noted above, as more water is drawn from the system at once, the velocity of the water flowing through the system increases, which causes pressure loss due to friction loss. That pressure loss reduces the ability of pump stations to pump water. Eventually, that is what happened here: the water that was reaching the three Palisades pumping stations had too little pressure to create the suction necessary to function, which caused the pumping stations to automatically shut down. With the pumps down, water was being drawn from the three Palisades tanks without being replenished. This led the tanks to eventually run out of water, too. By early morning on January 8, the three pumping stations had shut down and the three tanks had effectively run out of water.

As pumping stations lost pressure and tanks ran empty, there were reports that some hydrants in the Palisades-especially those in high-elevation zones that are serviced by the tanks lost pressure and water flow. Because hydrants do not have sensors, however, LADWP does not know exactly which hydrants lost pressure or when.

C. LADWP’s Efforts to Mitigate Pressure Loss

Throughout the fire, LADWP remained responsive to the needs of firefighters and the Palisades community. As soon as the fire began, the Water Operations Division began monitoring and responding to ongoing developments in real time. As the fire progressed, LADWP began activating its incident command response on January 7, 2025 at 1 :57 p.m., and fully activated at 3:55 p.m. The incident command team worked around the clock to address issues as they arose.

LADWP took multiple steps to make water available for firefighting. For example:

- LADWP made available to LAFD all of its open-air reservoirs throughout the entire water system, from which firefighting aircraft could (and did) draw water.

- LADWP attempted to install an additional valve to connect two pressure zones in an attempt to increase water pressure in the higher elevations in the Palisades. LADWP was unable to complete that work, however, because crews were directed to evacuate the area due to fire danger.

- LADWP deployed water tankers and trucks to the Palisades to make additional water available to LAFD. These vehicles, which were driven by LADWP drivers who worked in round-the-clock shifts, hold between 2,000 gallons and 4,500 gallons of water each. LAFD directed where in the Palisades these tankers and trucks should go based on their need.

- LADWP asked the Metropolitan Water District (MWD}-a water wholesaler that provides water to LADWP and other water districts-to open their nearby valve (called “LA-29”) to help increase flow and pressure. MWD did so on January 8 at around 7:30 p.m. Because MWD’s treatment plant was down at the time, and because the unprecedented level of demand was straining MWD’s system too, MWD closed the valve on January 9 at around midnight. We understand that MWD brought its treatment plant back online on January 10 at around 6:00 a.m., and reopened the LA-29 valve the same day at around 10:35 a.m.

- LADWP crews physically entered the affected areas to shut off water to access points where water was unnecessarily still running, such as structures that had burned down but had hoses and sprinklers running or whose pipes had been damaged and were leaking water. For instance, as structures collapsed, some pipes that serviced those structures were damaged, causing those pipes to leak substantial amounts of water. These open access points contributed to the unprecedented use of water, which increased the velocity of water in the system, which in tum reduced pressure in the system. Ultimately, LADWP closed roughly 4,800 access points in the Palisades that were leaking water.

III. The Santa Ynez Reservoir

SYR is the closest operational reservoir to the Palisades. At the time of the fire, SYR was drained and offline pending repairs to its floating cover.

Federal regulations require all operational, open-air reservoirs to be covered or for the water to be treated again on its way out of the reservoir. Floating covers, like the one at SYR, float atop the water and are attached to the reservoir at the sides. Their purpose is to protect the water from debris, animals, sunlight, and other things that could compromise water quality. By necessity, covers prevent access to the water by air-so the only way to access water in a covered reservoir is by distributing it through pipes into the distribution system. LADWP installed SYR’s cover in 2011.

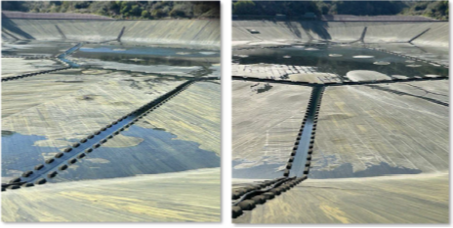

During an inspection in January 2024, LAD WP noticed a small tear-roughly a few feet-in SYR’s cover. Figure 3 below shows water ponding on top of the tear.

LADWP promptly notified its state regulator, the Division of Drinking Water (“DDW”) of the State Water Resources Control Board, and isolated the reservoir from the potable water system. On January 26, 2024, LADWP asked DDW for permission to place SYR back in service and continue using some of the water in it, subject to ongoing contamination testing. But DDW rejected the proposal to allow water from the reservoir into the potable water system, believing the likelihood of contamination in the reservoir water was too high. LAD WP began draining SYR in late February and finished in early April 2024.

In the meantime, LAD WP explored how best to repair the cover. Even though the tear that had been observed initially was bigger than any LAD WP had itself repaired before, in late January 2024 LADWP tentatively discussed the possibility of doing the work in house using LADWP crews. When LADWP again inspected SYR in early February, however, the tear had grown considerably-to about 100 feet. At that point, LAD WP confirmed that a tear of that magnitude is outside its expertise and capabilities, and decided to contract the work out. Figure 4 below is an aerial view of the tear before SYR was drained; Figure 5 shows the tear close up after draining.

LADWP also considered bringing the Palisades Reservoir back online while SYR was drained. Ultimately, the Palisades Reservoir-which, as noted, had been taken out of service about ten years earlier, and had an operational band of about 1.75 million gallons-could not be made operational at that time because it had water quality issues and needed repairs of its own.

From March to May 2024, LADWP completed the steps needed to publish a contracting bid. LAD WP published the bid on June 20, 2024 and closed it on July 10, 2024. There was only one bidder for $130,694. The contractor also agreed to train LADWP personnel while performing the repairs, so that next time LAD WP would be better positioned to do the repairs itself.

Over the next several months, LAD WP finalized the contract with the contractor. When it came time to schedule the repairs, the contractor indicated that it could not begin work until late January 2025 or early February 2025, which was after the Palisades Fire started. These repairs were ultimately completed in March 2025, and we expect SYR to be back online in June 2025.

# # #